|

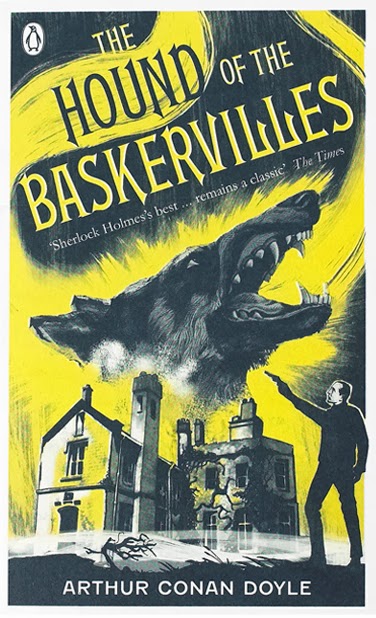

| Atmospheric poster for the 1939 adaptation |

Part II - Sherlock Holmes Goes to the Movies

By 1939, The Hound of the Baskervilles had already been adapted eleven times. There were two German versions in the 1910's and 1920's, two English versions (one featuring legendary Sherlockian actor Ellie Norwood, the other featuring the forgettable and lamentable Robert Rendel) and another German-made version made in Germany and released in 1937. This 1930's German adaptation was said to be a favourite of Adolf Hitler's and featured a bit of Nazi propaganda! Yet, none of these versions could hold a candle to the famed 1939 film made at 20th Century Fox, the first Sherlock Holmes movie to star Basil Rathbone as the detective. (For those interested in further trivia, 1939's Hound was the first Sherlock Holmes film set in the Victorian Era.) At the time of release, Fox wasn't known for horror films, the market being monopolized by Universal Studios, where the Sherlock Holmes series would soon emigrate. Yet, they did know a thing or two about movie detectives, and by 1939 Fox was running two highly successful detective series - the first being the exploits of Hawaiian detective Charlie Chan, based on the works of Earl Derr Biggers and the second being the adventures of Japanese detective Mr. Moto, as played by Peter Lorre and based on the novels of John P. Marquand.

Despite the fact that horror was not Fox's territory, the studio did an excellent job in capturing the essence of Doyle's novel. A great deal of their success is due to the massive moorland set which was constructed especially for the film. In a commonly believed anecdote, Richard Greene (the film's Sir Henry Baskerville) wandered onto the set and actually got lost. Whether this was true, or a clever bit of publicity, the set is moody with jagged rocks, swirling fog et al. Onto this imposing structure swaggers Rathbone's Inverness-clad, deerstalker-wearing detective, and the Victorian milieu, coupled with the gas lamps and hansom cabs glimpsed earlier add not only an aura of the fantastical but the cozy.

|

| Peter Cushing (right) and Andre Morrel (left) in Hammer Film's 1959 Hound adaptation |

By today's standards, Hammer's attempts to turn The Hound of the Baskervilles into an out-and-out horror film can come off as pretty campy. Nothing screams: "Look at how hard we're trying to scare you" as the opening scene in which David Oxley's venomous Sir Hugo Baskerville chases the servant girl across the moor, stabs her to death and his killed by the hound in an eerie point-of-view shot. Yet, things improve. The attempt on Sir Henry's life by means of a tarantula is pretty tense stuff (especially for this reviewer who has a deathly fear of spiders). Then, there's Stapleton, who becomes a revenge-seeking farmer with webbed hands, who performs a sort of sacrificial rite on Seldon the convict's corpse after the latter falls victim to the demon dog. The climax is relocated to a crumbling abbey on the moor, and the detective and doctor must stop the hound from worrying Sir Henry's throat as they're being threatened by a knife-wielding Stapleton. It's all pretty standard Hammer horror stuff - but I love every minute of it.

With just the right amount of overly-red fake blood and Technicolor, 1959's The Hound of the Baskervilles is the most bombastic adaptation of Doyle's famous story. In the years that followed, there were numerous other adaptations, most of which stuck closer to the source material than Hammer's. Yet, in doing so some of these films were so busy incorporating every one of Doyle's plot points, they forgot to make the film scary. The 1982 version starring Tom Baker and the 1988 version with Jeremy Brett fall victim to this slight error. but I'm glad to say that the most recent version of the story rectified problems, restoring the novel to its horror story roots.

|

| Benedict Cumberbatch and Martin Freeman on location in Dartmoor for The Hounds of Baskerville |

And so we come to the end of our journey - from The Hound of the Baskervilles' initial publication in 1901 to 2012. In that time, a scarlet thread of Gothic horror has run through its tangled skein of existence, easily making it one of the most beloved detective stories and horror novels ever written.